Introduction

Supporting autistic individuals is a complex task given the high prevalence of co-occurring conditions coupled with the significant variability in autism characteristics across individuals.1 This may result in misdiagnosis or underdiagnosis.1,2 It is crucial for medical professionals to have a deep understanding of autism, with limited knowledge and awareness of autism remaining significant barriers to accessing proper diagnostic and therapeutic support.3–6

In Malta, general practitioners (GPs) are often the initial point of contact for yet-undiagnosed autistic individuals who are struggling with difficulties that may be related to autism. Due to healthcare systems, psychiatrists are frequently involved with GPs, referring patients onwards for formal diagnosis and further care. Currently, there is no specialised diagnostic and therapeutic service for autistic adults in the national health service in Malta. Beyond the challenges specific to autism, Maltese medical professionals face additional pressures, such as an increasing population and growing multiculturalism, which can hinder timely access to appropriate care.7

According to data taken from the publicly available Maltese Medical Council’s Medical and Dental Specialist Register, 492 general practitioners and 64 psychiatrists currently hold a license to practice.8 However, determining the precise number of GP trainees was challenging due to variable annual intakes and a lack of publicly available data. 31 psychiatric trainees currently work within the public service. According to Eurostat data from 2020, the number of psychiatrists per capita is among the lowest in Europe at 11.06 per 100,000.9 This highlights the limited workforce available.

Internationally, a systematic review indicated that GPs in a majority of studies had inadequate knowledge of autism and the appropriate evidence-based interventions that may be required to aid autistic individuals.3 Another systematic review indicated low to moderate levels of knowledge and perceived self-efficacy about autism among health workers across a range of backgrounds.10 A UK study targeting GPs showed that despite demonstrating good knowledge of autism’s key features, participants reported limited confidence in their abilities to identify and work with autistic patients.11 A similar study targeting psychiatrists showed that though scoring highly in autism-related knowledge and reporting prior useful training on autism, respondents’ confidence in their ability to screen, diagnose, and aid their autistic patients ranged widely.12 Taken together, these results indicate that autism knowledge and perceived efficacy are highly variable across samples and individuals. Little is known about the knowledge and confidence of GPs and psychiatrists in Malta regarding autism. To explore these issues in a Maltese context, the authors conducted a survey examining GPs’ and psychiatrists’ knowledge and perceived self-efficacy in identifying and supporting autistic patients.

Methods

The researchers invited GPs and GP trainees, as well as psychiatrists and psychiatric trainees to complete an online survey catered to their area of specialisation between January and March 2024. Participants were recruited using convenience sampling methods, which included emails sent out to members of the respective medical associations. We also made use of Internet snow-balling methods with social media messages sent out to official groups of physicians. All data was collected anonymously. All participants provided informed consent to participate in this study which was carried out in conformity with the University of Malta Faculty of Medicine and Surgery’s Ethical Committee’s review procedures.

Each survey contained three sections, taking approximately fifteen minutes to complete. A copy may be found within Appendix 1. Part one comprised participants’ demographic details including age, sex, years in practice for fully qualified specialists, year of training if a trainee, and nationality. The survey also included questions as to whether that physician or a close relative had received a diagnosis of autism. Another question asked whether participants had received formal autism-related training as part of their medical degree and specialist training and how they would rate this. In their survey GPs were asked an identical set of questions as well as an additional question on whether they had any work experience in psychiatry.

Part two included a Knowledge of Autism Scale, originally described by Stone and subsequently modified to reflect an up-to-date scientific understanding of autism as adapted from surveys of UK-based GPs and Psychiatrists.11–13 Twenty-two statements assessed each participant’s knowledge of the early signs of autism, descriptive characteristics, and co-occurring behaviours. Responders rated these statements as ‘true’ or ‘false’. Scores on each item were summed to yield a total score; the higher the score, the greater the autism-related knowledge. A knowledge score was calculated, adjusting for chance responding using the following equation, in which R is the number of right responses, W is the number of wrong responses, and n is the number of items: R-W(n-1). Respondents’ scaled knowledge scores were expressed as a percentage of the total number of questions asked. This correction ensures that scores more accurately reflect true knowledge, minimizing the influence of guessing.14

Similar to previous studies on the knowledge of autism, the scale showed moderate internal consistency with a Cronbach’s 𝛼 of 0.54 for the GP and 0.5 for the psychiatry group. Although sharing a common focus on autism, statements vary from those tackling descriptive features, including method of diagnosis, prognosis, and possible interventions, to socioemotional and cognitive characteristics. This may account for the above result.

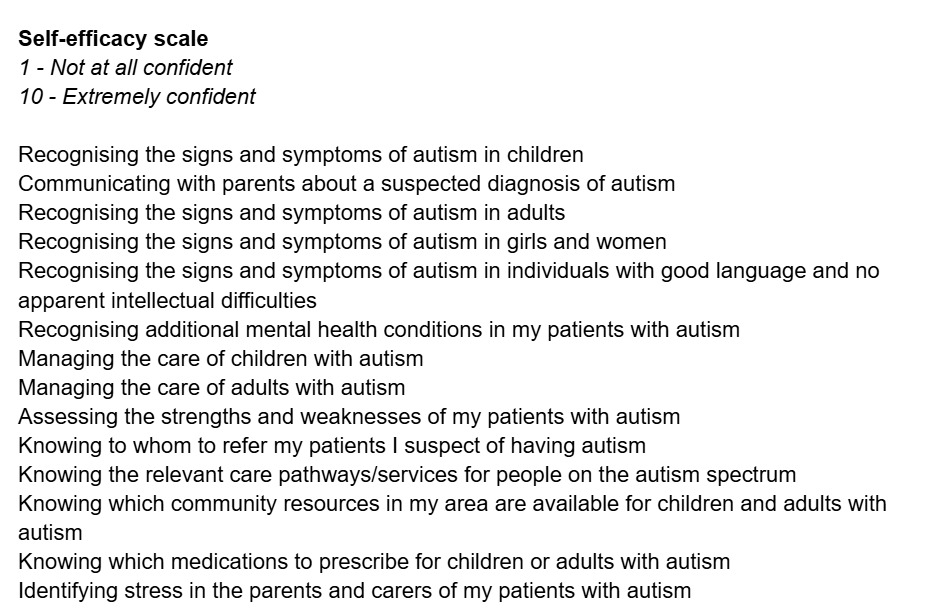

Part three of the study involved a self-efficacy scale designed to measure respondents’ confidence in screening, diagnosing, and providing support to autistic individuals. Perceived self-efficacy refers to individuals’ beliefs in their ability to achieve specific outcomes, varying depending on the context and matter in question.15 The scale used in this study was adapted from previous scales developed for similar purposes but was specifically tailored to assess GPs’ and psychiatrists’ perceived confidence in decision-making.11,12 The scale contained fourteen items with scores ranging from one (‘not at all confident’) to ten (‘extremely confident’). The average of these scores produced a mean self-efficacy score, where higher scores indicated greater self-efficacy. Given the structure of Malta’s healthcare system, the same self-efficacy scale was considered appropriate for both groups of specialists. The scale showed excellent internal consistency with a Cronbach’s 𝛼 of 0.92 for the GP group and 0.95 for the psychiatry group.

Data was analysed using SPSS version 29. Descriptive data analysis was conducted on the sample to provide an overview of the population characteristics. This included summarizing key demographic and clinical variables such as age, sex and years of experience using appropriate statistical measures such as means, standard deviations, medians and ranges. Results were presented in numerical and percentage form. Inferential data analysis included the independent sample t-test and its non-parametric equivalent Mann-Whitney U-tests as appropriate. The Hedge’s G statistic was used to determine effect size for difference between means with a correction for sample size discrepancy. Correlational analysis between the scores and different demographic variables was carried out using Pearson’s, Spearman’s correlation or ANOVA as appropriate.

Results

In total, 29 doctors within the psychiatry department and 69 doctors working within primary healthcare responded to the survey. All respondents completed 100% of the survey. Table 1 summarises the demographic characteristics of participants, which are elaborated upon in the following sections.

General Practice

With regards to GPs, all respondents were Maltese and most respondents were female (58% n=40), within the 21-30 age category (43.5% n=30), with 32% (n=22) being GP trainees whilst 68% (n=47) were fully qualified GPs. The majority of fully qualified GPs had been practicing for more than 10 years (59.6% n=28). Two respondents (2.9%) had received a personal diagnosis of autism, whilst 18.8% (n=13) had a first-degree relative previously diagnosed as autistic. The majority of respondents had no training in their primary medical degree on autism (52.2% n=36) as well as no training during specialist GP studies (58% n=40). Positively, the majority did have some experience working within a psychiatry setting before GP training (73.9% n=51).

Psychiatry

With regards to doctors working in psychiatry, all respondents were Maltese and most respondents were female (65.5% n=19), within the 21-30 age category (48.3% n=14) with 58.6% (n=17) being psychiatric trainees, whilst 41.4% (n=12) were fully qualified psychiatrists. A substantial proportion of fully qualified psychiatrists had been practicing for more than 10 years (40% n=6). None of the respondents had received a personal diagnosis of autism, whilst 13.8% (n=4) had a first-degree relative previously diagnosed as autistic. The majority of respondents (51.7% n=15) reported no training in their primary medical degree on autism. All respondents had received training on autism during their psychiatry training, with 41.4% of respondents (n=12) rating it as a ⅗ in terms of quality.

Knowledge of Autism scale

Table two outlines the items on the knowledge of autism scale and the percentage of psychiatrists and GPs that correctly answered each one. The mean knowledge score for psychiatrists was 89.2% (SD = 7.7) whilst that for GPs was 83.1% (SD = 8.5). The knowledge score for psychiatrists was higher than that of GPs and the difference was statistically significant (p = 0.0003, effect size g = 0.737).

Analysis of the individual items on the Knowledge of Autism Scale revealed a wide range of correct response rates among both psychiatrists and GPs, ranging from 20.7% to 100% for psychiatrists and from 23.2% to 100% for GPs. Notably, the statement “An autism diagnosis cannot be made before a child is 3 years of age” had the lowest correct response rate, with only 20.7% of psychiatrists and 23.2% of GPs answering correctly. A further example of group variation was seen in the item regarding autism prevalence in adults versus children, where 69.0% of psychiatrists answered correctly compared to only 37.7% of GPs. Across most items, psychiatrists demonstrated higher accuracy than GPs. Differences of more than 20 percentage points were evident in questions on familial recurrence risk and the association between autism and intellectual disability. These patterns indicate both inter-group disparities and substantial intra-group variation in domain-specific knowledge.

Psychiatrists’ scaled knowledge scores were not significantly correlated with age (p = 0.75), sex (p = 0.45), years practicing for qualified psychiatrists (p = 0.27), years of training for trainees (p = 0.06), or autism training received during medical school (p= 0.63). However, having an autistic relative correlated with lower scaled knowledge scores (r = - 0.56; p = 0.0017).

GP’s scaled knowledge scores were positively correlated with having received training on autism in their medical school years (r = 0.25; p = 0.03) or in their GP training programme (r = 0.33; p = 0.005). Scores were also positively correlated with having experience working in psychiatry (r = 0.32; p = 0.007). GP’s scaled knowledge scores were not significantly correlated with their age (p = 0.18), sex (p = 0.41), years of practicing for qualified GPs (p = 0.93), or years of training for GP trainees (p = 0.149). They were also not correlated with having an autism diagnosis themselves (p = 0.20) or having an autistic relative (p = 0.13).

Self-efficacy scale

Table three shows the mean score for each item in the self-efficacy scale for psychiatrists and GPs. The mean self-efficacy score was 6.7 (SD = 0.4) for psychiatrists and 5.7 (SD = 0.8) for GPs with the difference showing statistical significance (p=0.0003, effect size g = 1.414).

Analysis of the self-efficacy scale revealed considerable variability in confidence levels across both psychiatrists and GPs, with mean item scores ranging from 5.8 to 7.4 for psychiatrists and from 4.6 to 7.5 for GPs. The greatest discrepancy between the two groups was observed in prescribing medications for autistic individuals, where psychiatrists scored a mean of 6.9 compared to just 4.6 among GPs. Confidence in recognising autism in adults was also markedly lower among GPs (mean = 5.6) than psychiatrists (mean = 6.8). Conversely, both groups reported higher confidence in knowing whom to refer suspected autistic individuals to, with GPs even slightly outperforming psychiatrists (7.5 vs. 7.2). Psychiatrists reported highest confidence in recognizing signs of autism in children (mean=7.24) and in knowing referral pathways (mean=7.21). The lowest confidence was reported in offering appropriate care for autistic children (mean=6.38) and adults (mean=6.48), reflecting specific clinical challenges in identifying and carrying out appropriate evidence-based interventions.

Psychiatrists’ mean self-efficacy scores were not significantly correlated with age (p = 0.09), sex (p = 0.78), years practicing for qualified psychiatrists (p = 0.92), training received during medical school (p = 0.13) or having an autistic relative (p = 0.09). GP’s mean self-efficacy scores were positively correlated with autism training received during GP training (r = 0.37;p = 0.002), years of training for GP trainees (p < 0.001), experience working in psychiatry (r = 0.36; p = 0.002), and having an autistic relative (r = 0.25; p = 0.04). GP’s mean self-efficacy scores were not significantly correlated with age (p = 0.47), sex (p = 0.49), years of practicing for qualified GPs (p = 0.19), , training received in medical school (p = 0.14) or them having an autism diagnosis (p = 0.54). In both groups, there was no significant correlation between knowledge of autism scales and self-efficacy scales (Psychiatry p = 0.26; GP p = 0.14).

Discussion

Main findings

Findings indicate that Maltese doctors demonstrate an overall good knowledge of autism and moderate confidence in working with autistic patients. Compared to their UK counterparts, Maltese GPs scored slightly lower on knowledge (83.1% vs. 87.8%) but higher on self-efficacy (5.7 vs. 5.4).11 Maltese psychiatrists had a mean knowledge score of 89.2% and a self-efficacy score of 6.7. In comparison, UK psychiatrists had a mean knowledge score of 91.0% (SD = 6.5), and their self-efficacy ratings varied by task—for instance, only 33% reported feeling confident in diagnosing autism, and 47% felt confident in supporting autistic adults.12 These figures suggest that while knowledge levels are similar across contexts, confidence is more task-specific and variable in the UK cohort.12 Due to the self-reporting nature of responses, despite having an overall lower knowledge score in comparison with UK colleagues, Maltese practitioners may be overestimating their efficacy in working with autistic patients. This may be explained by the Dunning-Kruger effect, a cognitive bias whereby those with limited competence in a particular domain overestimate their abilities.16

The significant intra-group variation in both knowledge and self-efficacy—even among psychiatrists—suggests that informal or incidental learning may be insufficient. Instead, structured, standardized, and locally contextualized training may yield better outcomes, especially as targeted training has been shown to improve outcomes for autistic individuals.17 Across both groups, self-efficacy was highest for interpersonal and communication tasks, highlighting that practitioners may perceive personal strengths in their communication skills and patient relationships. Conversely, lowest scores were provided for tasks involving medical decision-making or adult-specific care. These findings highlight uneven preparedness across clinical domains and suggest that expanding training to cover adult presentations, gender differences, and pharmacological aspects could improve both knowledge and confidence.

Among Maltese GPs, mental health training, and work experience, such as placements in psychiatric settings, were positively correlated with both knowledge and self-efficacy, further underscoring the importance of targeted mental health training to build competency. Currently, GP trainees receive only four weeks of psychiatric placement during their three-year training programme in stark contrast to the relatively longer time spent in other medical disciplines. A longer rotation could aid in building knowledge and self-efficacy for the betterment of the trainee’s experience and the future care they will provide.

The lack of a single identifiable factor linked to improved knowledge or self-efficacy among those with postgraduate training in psychiatry may be attributed to the small sample size of this group. There may also be an element of response bias, such that those who chose to answer the survey may already hold a special interest in autism and thus exhibit better knowledge and self-efficacy. Conversely, those who chose not to respond may exhibit the converse. Interestingly, those with a personal connection to autism scored lower in terms of autism knowledge. These doctors may not appreciate the full spectrum of autism, instead focusing on their personal rather than clinical experience. This counterintuitive finding may reflect that lived experience does not equate to clinical expertise, highlighting the distinction between personal and professional knowledge and further underscoring the importance of education.

Furthermore, psychiatric trainees, whilst exposed to a young people’s neurodevelopmental diagnostic and clinical service, receive no such similar experience for service users over 18, leaving a clear lacuna in clinical experience. There is no current structured teaching regarding neurodevelopmental conditions in postgraduate psychiatry training, which relies rather on trainees carrying out studies in their free time or ad hoc lectures. A structured, multi-faceted approach in postgraduate psychiatric and general practice education could support holistic skill development among Maltese doctors. This could equip doctors with the knowledge and confidence necessary for working effectively and sensitively with autistic people.

Strengths and Limitations

This survey represents the first attempt to focus on general practitioners’ and psychiatrists’ knowledge, experience, and confidence in working with autistic patients in Malta. It is not, however, without its limitations. The sample size was fairly low. As a small island nation with general practice and psychiatry having one respective department each, the number of possible doctor participants is low. Though the sample size may have been small there was a good representation of doctors with different levels of work experience and different demographic characteristics.

Secondly, given that several respondents reported having some personal connection with autism the sample may be biased, with those with a keen interest in autism being more likely to respond. Finally, the tools utilised above were not translated into the Maltese language. However, the Maltese Doctor of Medicine and Surgery degree is taught entirely in English and English is one of Malta’s two native languages. Thus, it is assumed that all participants had an adequate grasp of the English language to answer competently.

A further limitation lies in the interpretation of self-efficacy scores: while this study found associations between training, experience, and higher confidence levels, it does not establish that greater self-efficacy leads to improved patient care. Although higher self-efficacy may reflect perceived competence, it may also overestimate actual clinical performance, particularly in the absence of observational or outcome-based validation. This highlights the need for future research linking provider self-efficacy with objective measures of diagnostic accuracy and patient outcomes.

Implications for research and practice

The findings of this study provide direct evidence that autism-specific training and tailored work experience significantly enhance general practitioners’ knowledge and confidence in supporting autistic patients. Conversely, the wide variation in self-efficacy—particularly among GPs—points to a need for more structured, evidence-based education on autism in both undergraduate and postgraduate medical curricula in Malta. Importantly, while higher self-efficacy scores were observed in those with more training, this study cannot confirm that increased confidence translates into improved patient outcomes. This highlights the importance of designing future research that investigates the relationship between perceived efficacy and clinical performance or patient satisfaction.

Involving autistic people in service development projects leads to a better quality of care.18 In Malta, the lack of local research on the prevalence rates of autism represents a significant gap in understanding the scope of the country’s need to deliver effective, targeted interventions.7 Furthermore, research focused on local autistic adults’ experiences could identify barriers and limitations when accessing and receiving healthcare, and thus aid in tailoring physician training and healthcare services to meet these needs.

Women and girls are often underdiagnosed due to gender differences in presentation.19 Our research highlights the difficulties faced by Maltese GPs who felt only somewhat confident in recognising the signs of autism in adults, especially women, whilst feeling more confident about recognising these signs in children. Training concerning updated scientific knowledge on autism and gender-specific presentations could aid in ameliorating this.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that Maltese GPs and psychiatrists possess strong foundational knowledge about autism, yet show inconsistencies in clinical confidence, particularly in the identification of autistic individuals and decision making related to pharmacological interventions. The notable variability in self-efficacy among both psychiatrists and GPs underscores urgent training needs and specifically targeted training.

On a local level, there is a critical need for the development of adult diagnostic services for autism, as well as specialized clinics for autistic adults within public health care systems.7 The lack of services is particularly concerning given the lower confidence levels among GPs in recognising and supporting their autistic patients. This research underscores the urgency of developing such services and integrating multidisciplinary autism care pathways into primary care settings, coupled with appropriate training. These services are essential not only for accurate diagnosis and early intervention but also for providing tailored support throughout an individual’s life.

Investment in more training and effective services could reduce the reliance on psychiatric tertiary services, particularly during times of crisis, and enhance the overall mental well-being of autistic individuals and their families. Policymakers and medical educators should use these research findings to inform curriculum reform, continuing professional development, and the expansion of clinical services that are responsive to the unique needs of autistic individuals in Malta. Improving access to appropriate, knowledgeable, and person-centered care is essential for fostering a more inclusive healthcare environment and ensuring better outcomes for autistic people across their lifespans in Malta.